The Theory of Constraints as a Metaphor for Credit Limit Management

When a manufacturer wishes to improve the efficiency of their operation they can turn to a wide range of proven tools and techniques. There are tools to assist with the optimisation of production schedules, the minimisation of inventory, the reduction of waste and any number of other common causes of inefficient operations. Many of these systems have been successfully adopted by service businesses. However, when adopted, they are seen primarily as a means to optimise the physical interactions which deliver the service, rather than as a means to improve the service itself.

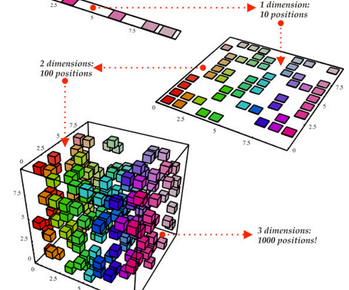

One of the most successful of these theories is Eli Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints. Goldratt shows that the performance of a whole system is dictated by the performance of the slowest individual component of that system. It focuses its efforts, therefore, on identifying and alleviating that constrained resource – or the bottleneck in the production process – because the performance of the system is optimised whenever the performance of the constrained resource is optimised. Every system must have at least one such constraint because, in the absence of such, a profit-making organisation would make infinite profits. Constraints are seen as positive as their existence represents an opportunity for improvement. Consequently, a continual improvement in system constraints will result in a continual improvement in organisational results.

The Theory of Constraints has found broad support from service businesses – including banks. However, as with all such theories its application has been limited to opportunities to increase the efficiency of the service delivery processes. A bank might, for example, use it to reduce the time it takes to process a loan application. However, even more value could be created if banks were to use it to improve their products too – in this case the loan itself.

In a simplified manufacturing scenario we would expect to find machines that turn ‘inputs’ into ‘outputs’ (the rate at which they do this is called ‘throughput’), some ‘working capital and some damaged goods or ‘scrap’. It is easy to see how a theory originating in this environment might be applied to the service delivery process – the staff become the machines who, by using their training, systems and other ‘inputs’, deliver the service or ‘outputs’. It is less easy to see how they might be applied to service design process. To do this, we must look at things from a new angle.

Consider a simple manufacturing business with three machines turning inputs into outputs: one with very high throughput but low accuracy, one with low throughput and high accuracy and one that falls somewhere between those extremes. The first machine creates finished products more quickly than the other but also creates the most scrap. The second machine creates little scrap but also few outputs. Another consequence of the slow throughput rate is a build-up of inventory and its associated costs. The third machine produces a more optimal mix of finished products and scrap.

This set-up can be a better metaphor for an unsecured loan product than might be expected. Instead of machines, banks have credit extensions which, in lieu of turning inputs into outputs, turn excess capital into interest bearing balances. Instead of a throughput rate there is a limit utilisation rate, risk replaces accuracy and bad-debt write-offs replace scrap. So we can translate the earlier manufacturing example into banking terms.

The first credit portfolio has a very high utilisation rate but also very high risk, the second portfolio is of very low risk but has a very low utilisation rate and the third portfolio is, once again, a balance of the two extremes. The first portfolio might lead to more balances in a period but it comes at the high cost of significant bad-debt write-offs. The second portfolio might have almost no bad-debt write-offs but it also struggles to create interest bearing balances leading to a build-up of inventory in the form of unproductive capital. The third portfolio creates a better mix of interest bearing balances and bad-debt.

This contrived scenario is clearly overly simplified. However, real data from a major retail bank has revealed a similar pattern. The lowest risk accounts tend to have very low utilisation rates and thus carry large inventories of unproductive capital. On the other end of the scale, the utilisation rates were at their highest but so was the rate of bad debt write-offs. The most profitable accounts were found somewhere between these two extremes where an acceptable levels of risk coexisted with an acceptable utilisation rate.

Unless a metaphor helps us to more clearly understand a problem it is simply interesting, not useful. So, in order for lenders to gain benefit from the manufacturing metaphor it is important to move past the descriptive stage and actually put theories like the Theory of Constraints to use when designing a loan product so as to achieve a portfolio with a better mix of risk and reward.

The Theory of Constraints has a specific set of steps to identify and remedy under-performing components in a system – called the ‘framing steps’.

The first of these framing steps is to articulate the goal which, in this case, is to maximise the profit generated by a given portfolio of loans. Not all portfolios are purely profit focused but in most cases this will suffice. (To read more about how each component of the lending process contribute’s to a lender’s profit, read this article on the subject of profit model analytics)

The second step is to identify the constraint. As the name suggests, Eli Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints spends a lot of time in this area; the constraint – or bottleneck – in a process is that component that is most under-stress and that is most hampering the performance of the process as a whole. In our example, there was a high level of unused capital (inventory) in the lowest risk groups – as often occurs when credit is provided on risk criteria alone, independent of any demand indicators. A build-up of inventory is a sure sign of the existence of a constraint and so, in this case, the bottleneck is the level of market demand.

Having identified the constraint, the next steps are to exploit the constraint, to subordinate all the other processes to the constraint and to elevate the constraint. In layman’s terms, this means the work being done by the constrained process is prioritised and non-essential tasks are removed or relocated to non-constrained resources. Then, all other processes are adjusted and aligned to accommodate those decisions. In terms of a portfolio of loans, this could involve adjusting pricing and reallocating capital to the riskier accounts where demand is higher.

Finally, investments must be focused on improving the capacity of the bottleneck – by offering incentives for low risk customers to borrow, for low risk customers to transfer balances, etc. Once the constraint has been thus removed, the process repeats itself identifying and removing the next constraint. Thus, a process of continuous improvement is born.

I have hardly done the Theory of Constraints justice in this article and anyone interested in exploring the concept in more detail should read Eli Goldratt’s The Goal – his very readable business novel in which the concept is introduced and expanded upon.

Regardless, I hope that this high-level investigation has given some insight into how one can apply learnings from diverse fields in a way that both explains credit risk concepts in more widely understood terms and that offers new inspiration for problem solving.